We’ve been talking about the strength of the American workforce this week and the resiliency we’ve seen from people around the country in various industries as they respond to recent events — Laurie’s hotel, Patti’s PPE manufacturing, Peter’s pipeline. Each one has had to retool or rethink their career plan and skills in some way over the last year.

Another industry that has felt the pandemic strain is supply chain and logistics. We were forced to confront the fact that our global supply chain wasn’t as strong as we may have thought. Domestically, we’re now seeing many supply chains being disrupted by factories and warehouses low on workers.

Today, we want to share some perspective from a company in Cleveland, Ohio that started a workforce training program in the middle of last year — at the height of the pandemic — in supply chain and warehouse logistics.

In 2015, Andre Bryan launched BridgePort Group, an African-American, veteran-owned small business that specializes in global supply chain consulting, warehouse distribution, logistics technology, and related certification training programs. He has been training for years at the corporate level — larger corporations and companies would send their project managers and other employees to Andre for training and various certifications.

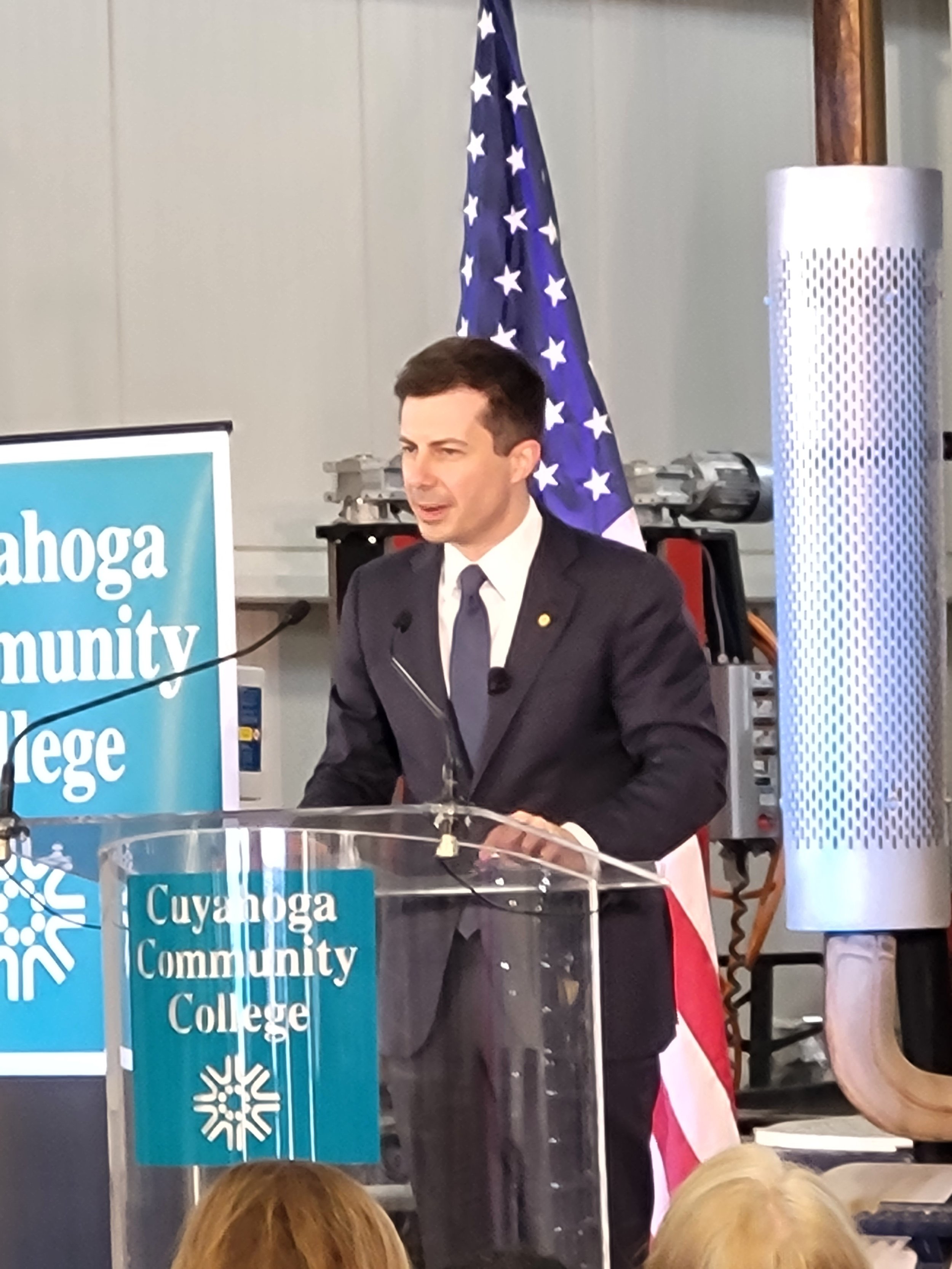

In the middle of 2020, BridgePort Group partnered with a local community college and developed their Supply Chain Logistics Technology and Warehouse (SCLT&W) pre-apprenticeship course designed to develop a qualified workforce to attract higher entry level wages, and to put students on the path to advancement within the growing supply chain industry. Initially, it was created to ensure BridgePort Group had a pipeline of qualified workers in their warehouse, but they quickly saw where their training could fill a need in urban and rural parts of Northeast Ohio. Those who complete the SCLT&W program receive four in-demand certifications that are transferable to multiple positions throughout the supply chain and related industries.

Andre knows personally the frustration of going through a job training program and there being no job at the end, which he says is an issue he’s found with many other similar programs in the area. “What we do is try to get sponsors for the program upfront, so that when we train the students, we can customize them for the workplace they’ll probably end up going to,” Andre told us. The current training is specifically geared toward the Cleveland Clinic, which is seeing a need for more warehouse and logistics workers for their PPE supply chain.

“We have one participant who is 18 and never finished high school but just recently got his GED. He’s excited because he can see a pathway forward that’s not a McDonald’s job or hanging out on the streets. He can say ‘Hey, there’s a major hospital system right around the corner from my house called the Cleveland Clinic that is interested in hiring me because of all these certifications that I have.’”

Another program participant is a college-educated man in his late 40’s who was recently laid off from his job of 20 years as a transportation manager and is now seeking this new education and these certifications to make him more employable as he re-enters the workforce.

“Our vision is to give people the opportunity to walk into a job with more tools in their toolbox. It allows them to ask for higher entry jobs and better wages,” said Alex Harper, a project manager at BridgePort Group. “Economic development doesn’t come overnight. Low-income communities remain that way due to a number of factors including lack of education and training opportunities, non-promotion or dead end jobs with non-livable wages, no realistic career path, and few sustainable job opportunities.”

But given a chance at these opportunities, Alex continued, people can then support and grow their communities by investing there, or it allows them to get out of situations or communities not serving them.

The pandemic reminded us that everything runs on our supply chains — from DoorDash to Amazon to our grocery stores. These are industries where lower income communities aren’t moving up to higher levels of the job, Alex and Andre explained. “They’re at the entry level warehouse position, but they’re not able to get to that management, corporate level, because they don’t have a lot of the necessary formal training.” BridgePort Group’s certification training and workforce development gives them the opportunity to advance within their organization, or the opportunity to leverage their skills elsewhere.

“Historically the problem in urban communities, disadvantaged communities, and rural communities is that in those areas, there’s a limitation on the types of jobs you can get and the skills that you get after high school, that is if you finish high school,” Andre said. “It is typically limited to a small industry. If you can gain some skills in the supply chain field, it just opens up a huge opportunity, because supply chain entry level jobs are 20-25% higher paying than other entry level jobs. The wages are sustainable wages with promotion paths.” Participants of the SCLT&W program are exposed firsthand to over 50 careers of the nearly 300 or so related to supply chain logistic technology and warehouse management — and they’re all high paying.

BridgePort Group plans to expand the program with more students and some specialized training designed to anticipate future trends in needed skills for the 21st century workforce. Look no further than Andre, Alex, and their program trainees to find Americans providing and taking advantage of opportunities to better their communities, and the country.

Additionally, Andre Bryan is the Small Biz representative of the Infrastructure bill subcommittee on Capital Hill and has presented the program to Congressman Donald Payne who heads up the subcommittee. “I plan to get an endorsement from him or his staff in the near future and expand the program to the NY/NJ area as well as west coast with the help of Congressman McCarthy.”